‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’: Its Onsite and Online Dissemination and How does it Speak to Art in Crisis

The 13th Annual Conference

Centre for Chinese Visual Arts

8-9 November 2020

The 13th Annual Conference

Centre for Chinese Visual Arts

8-9 November 2020

‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’: Its Onsite and Online Dissemination and How does it Speak to Art in Crisis

Thank you for having me here. I am Xiaoyi, a last year phd in Royal College of Art in Curating Contemporary Art. Today I will about an action and also online event, ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang.’ I hope to firstly provide a detailed and accurate account of this action on site and online that culminated into a national event. Secondly, I will draw onto the work to discuss, why a crisis in the society transform into a crisis in art in China during the pandemic?

First, let us roll back the time to February, 2020.

![]()

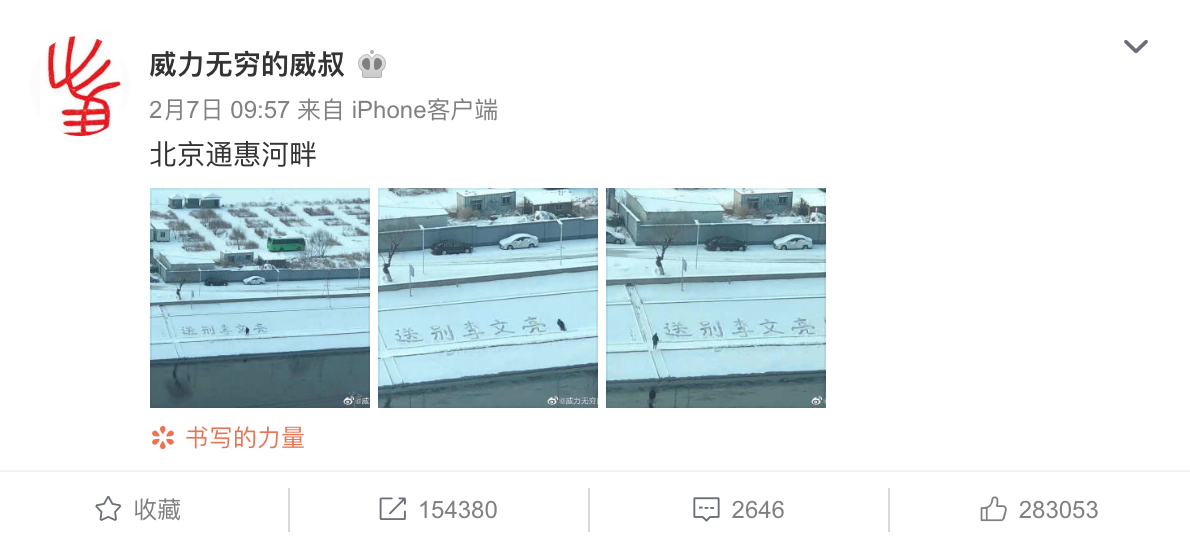

Screenshot of the Weibo post on 8 Feb 2020

1

Most people knew about this action through a post published by Weibo account ‘weiliwuqiong de weishu’ (‘Almighty Uncle Wei’ 威力无穷的威叔) on 9:57 am on 7 February. The text briefly says ‘The bank-side of Tonghui River, Beijing’ (Beijing tonghuihepan 北京通惠河畔). There are three horizontal images. The first one overlooks the ground from a vantage point: in up one-thirds of the image, a large area of land was covered in snow; there are several bungalows, neatly arranged squared bushes and cars adding some grey and brown touches to the image, and a long grey wall enclosed the bushes in a huge yard. The bottom section is the Tonghui River that might have frozen slightly on the surface, reflecting the bare willow on the bank. Then we focus on the riverbank, the geometrical long white stripe, composed by several segments of slopes. A person in a black coat was standing on the narrow path between the slopes, in front of five giant Chinese characters clearly inscribed into the snow. The air is fresh as everything demonstrates its clarity. It seems to be a quiet winter morning. Apart from this person, no one else was there. In the second image, the lens pushes up, and we find the man lying by the side of the characters. His body in black is in the snow, parallel with the characters. In the third photograph, the man stands along the stairways, looking at his final work before leaving the site. It has also become clear now that what the shape of his body in the snow has left an exclamation mark. The five Chinese characters, says, ‘farewell to Li Wenliang’送别李文亮. Later a video also came out on the Internet. It shows that the man let the gravity draw his body fall into the snow and he squatted down to make a firm round point of that exclamation mark.

According to the weather forecast, Beijing was -8℃ ~ -3℃ that day, with moderate snow.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Who is Li Wenliang? You might have heard about his name before. He was praised as the whistleblower of the pandemic. He was a doctor in Wuhan Centre (zhongxin) Hospital. He reminded people in Wechat groups to take cautious procedures before the official announcement. He was one of the seven doctors who were criticised by the local police for divulging information without the authorised permission. He was celebrated as a civilian hero who acted according to his conscience. The night before 7 February, Li passed away because of coronavirus. That long night was the saddest Internet timeline I have ever seen. Li passed away at a time when the country was still in a state of emergency of mass-scale mobilisation and strict lockdown, and there was a shared emotion, a mixture of desperation, anger, sadness, willing to fight, mutual care and alliance. The passing away of Li, to some extent, became a breakthrough for these emotions.

When the news of Dr. Li’s death came out, the mourning occupied the landing page and the time line on my Weibo. Later, this post of ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’ came out and it was kept being reposted by hundreds and thousands of people, becoming a sign for the shared sadness and mourning. That synchronised and relayed action of reposting in the virtual public space, reminded me of Judith Butler’s discussion about the ‘public assemblies’ in Tahrir Square and on streets in Hong Kong in her book Notes toward A Performative Theory of Assembly. Reposting together turns into a visual form and at the same time, a political form demonstrating the mobility and alliance based on the network of virtual connection. Until 27 October, this post has been reposted more than 154 thousands of times and there has been other circulation on platforms like Weixin. Like most people, I came across these images on the social media. Despite the fact that I was not in China, I was synchronised with the waves of information and mood on the Chinese Internet 简中互联网. When looking at the Weibo timeline filled with these images, I was speaking to myself, ‘this is the political moment in my generation.’

But I was also thinking, among all the mourning, why did this action and these images receive the most reverberation? Is this related to the fact that it was a physical action? Or because it has a slogan-like demonstration? When Butler discusses street politics, she emphasises the importance of embodiment. She asks, ‘could we still understand action, gesture, stillness, touch, and moving together if they were all reducible to the vocalization though speech?’ (Butler, 2015, 87) For me, this action Farewell to Li Wenliang reclaimed the right to physical spaces, to bodily actions as well as to silence. During the lockdown, the digital space was anxious, crowded and clamorous; if you don’t make a sound or type what your think, there would be no signal of your existence. When the man in black coat was lying down and gazing into the sky, there was the silence that could not be vocalised in another form. At the same time, this act was highly personal, as an individual’s creative response to the death of Dr. Li. It seems that he was not expecting a feedback, nor has he claimed authorship of the action. It is this personal and anonymous nature, combined with the penetrating and monumental form, paved the ground for the unpredictable publicness. It resembles to a grand political slogan in public spaces in China. But when realising that exclamation mark has been written by the man’s body, this slogan then is transformed into a resolute and decisive declaration. To some extent, it was an alarming reminder for people: right now, the most important thing is to say farewell to Dr. Li Wenliang, to pay your tribute, to say thanks for what he had done, to mourn for him.

Despite this action has been widely circulated, the basic information about it has been unclear. People generally consider the account that posted the images is the author, but it was not confirmed. And we are not sure if there was any mediation between the action and the documentation. After some time of searching, I found the original author who took these photographs, a witness of this action, and I did an interview with her. She would love to be called as ‘Ferris Wheel Maintenance Man’ (修摩天轮的). She was a young photographer in Beijing and lived opposite to that riverbank on a high-rise. On the morning of 7 February, to be more accurate, 8:56 am, she spotted the action when it was ongoing, captured it with her smart phone and shared these photos with several friends. These images then spread through personal networks and when they were posted online nearly one hour later, this action became a national phenomenon. In this sense, the man who did this action, the photographer and people who shared it, are all contributors in transforming an anonymous and spontaneous action to an ‘event’ without any mediation. Later in that day, there were some bunches of fresh flowers left on that site. And in the afternoon, when the clouds in the sky dispersed, the photographer saw that man in black came back again. He stood by side of the characters, looking at it in the sunshine then and slowly walked away along the river. Later, more writings also came into existence on the riverbank, they were saying, ‘Go Wuhan’ (武汉加油) ‘China will succeed’ (中国必胜).

![]()

![]()

2

How this event has happened is not a mystery. But the action itself has a resolution and strength, which inspires me so much in thinking about art. This action itself did not take place in an art context; not all people consider it as art. For example, the photographer is against calling it art. In the following section, I want to first acknowledge this action does not claim to be an artwork, but I will then draw onto the strength of this work, to think about the suspicion and disbelief in art among Chinese artists and art-workers during the pandemic.

Among all the art genres that we could describe ’Farewell to Li Wenliang’, on-site performance and online art engagement might be the most obvious tags, but such clarification emphasises more on certain medium or about the platform like Weibo and Instagram. I would also call it as a performance, but I hope to position it into the history of Dada or the frenetic behaviours of ancient Chinese liberati like 阮籍, in the sense that it is expressing a political and social concern in a highly personal and creative approach. I hope to borrow scholar Jonah Westerman’s definition: performance is ‘a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world’ instead of a medium about body or acting. It is actually the undefined and nonconforming state of the work and its relation to the world, especially to me, it is my experience of being inspired and haunted by it, makes me claim this work is a brilliant artwork.

Back to February, China was the first country that fell into the state of national lockdown. For most residents in China, their lives were also suspended and I observed a widely spread suspicion towards art among Chinese artists and art workers when looking at Friend’s Circle on Wechat or Weibo. Some artists stopped their work because they could not access their studios; while some lost their faith in doing art. In late January, Art Newspaper Chinese sent out invitations to artists and asked if they could make a piece, do something or write something, many declined. A discussion was also heated, about Theodor W. Adorno’s famous sentence ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’. Many considered it as inappropriate to work on art and literature in a time of catastrophe. However, later when Europe and the US entered into the lockdown, I did not observe the same degree of suspicion or caution towards art. This led me to question, why did the Chinese artists feel awkward in the situation? How did the crisis of the society become an art crisis for these Chinese contemporary artists, according to my very biased observation?

![]()

![]()

The artists’ caution to the political climate reminds me of the 1990s, when some Chinese artists intentionally turned away from themes like ‘Chinese identity’ and ‘feminism’, because they were afraid that their art would become a political pose and fall into the trap of ‘playing the identity card’. But I hope to point out that this time is not only about distancing from the politics. Rather, some of the depression actually emerged from the inability to engage with the society: many artists’ in fact have deep concerns and almost a sense of responsibility to engage lively. In China, there is a long mainstream tradition that literary arts interconnect with the politics and society. In the ancient time, the literati in the elite class with political power and ambition also made ‘political art’ in today’s view, like calligrapher 颜真卿; in the modern time, Mao Zedong’s ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art’ (1942) 延安文艺座谈会上的讲话 stresses art should be made for ‘the masses of people’; since the 1980s, though contemporary art in China is often depicted as victim of censorship, artists were actually also active in engaging with the ideology, the society, especially when many of them were also intellectuals. C. T. Hsia, 夏志清 a founding scholar in the history of Chinese modern literature, considers that the Chinese literature works from 1917 to 1949, were haunted with great concerns and there was a moral sense in the society and an ‘obsession with China’ 感时忧国. I think many contemporary artists in China also share this strong concern over society and have carried this into their works. In short, in my opinion, this art crisis is in fact, a combination of turning away from politics, and at the same time, the sense of responsibility of engaging in politics during the time of the pandemic.

What I am trying to make out of from the action ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’, is not about whether this action is art or not, but rather, why artists should still trust in art. This action shows us that how much people are still in need of an imaginative, penetrating and healing expression especially in the time of difficulty; and how much hope and solidarity it could bring across isolation. It also reminds, great art, no matter it is made when facing the society or in solitude, all emerges from a profound and solid understanding to humanity and the world. If the photographer did not capture the action, if no one has seen it, if only the river and the sky have been the witness and the snow melted down and no trace of the words is left, will the power of this action be diminished? My answer is a clear No. It stands in its own history, responding directly to the death of Dr. Li Wenliang. The man in the black coat, no matter what happens, he is that bearer of his action. As for the audience, I think, we are just the lucky ones, sharing the power that he has inscribed into the snow.

Thank you.

Thank you for having me here. I am Xiaoyi, a last year phd in Royal College of Art in Curating Contemporary Art. Today I will about an action and also online event, ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang.’ I hope to firstly provide a detailed and accurate account of this action on site and online that culminated into a national event. Secondly, I will draw onto the work to discuss, why a crisis in the society transform into a crisis in art in China during the pandemic?

First, let us roll back the time to February, 2020.

Screenshot of the Weibo post on 8 Feb 2020

1

Most people knew about this action through a post published by Weibo account ‘weiliwuqiong de weishu’ (‘Almighty Uncle Wei’ 威力无穷的威叔) on 9:57 am on 7 February. The text briefly says ‘The bank-side of Tonghui River, Beijing’ (Beijing tonghuihepan 北京通惠河畔). There are three horizontal images. The first one overlooks the ground from a vantage point: in up one-thirds of the image, a large area of land was covered in snow; there are several bungalows, neatly arranged squared bushes and cars adding some grey and brown touches to the image, and a long grey wall enclosed the bushes in a huge yard. The bottom section is the Tonghui River that might have frozen slightly on the surface, reflecting the bare willow on the bank. Then we focus on the riverbank, the geometrical long white stripe, composed by several segments of slopes. A person in a black coat was standing on the narrow path between the slopes, in front of five giant Chinese characters clearly inscribed into the snow. The air is fresh as everything demonstrates its clarity. It seems to be a quiet winter morning. Apart from this person, no one else was there. In the second image, the lens pushes up, and we find the man lying by the side of the characters. His body in black is in the snow, parallel with the characters. In the third photograph, the man stands along the stairways, looking at his final work before leaving the site. It has also become clear now that what the shape of his body in the snow has left an exclamation mark. The five Chinese characters, says, ‘farewell to Li Wenliang’送别李文亮. Later a video also came out on the Internet. It shows that the man let the gravity draw his body fall into the snow and he squatted down to make a firm round point of that exclamation mark.

According to the weather forecast, Beijing was -8℃ ~ -3℃ that day, with moderate snow.

When the news of Dr. Li’s death came out, the mourning occupied the landing page and the time line on my Weibo. Later, this post of ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’ came out and it was kept being reposted by hundreds and thousands of people, becoming a sign for the shared sadness and mourning. That synchronised and relayed action of reposting in the virtual public space, reminded me of Judith Butler’s discussion about the ‘public assemblies’ in Tahrir Square and on streets in Hong Kong in her book Notes toward A Performative Theory of Assembly. Reposting together turns into a visual form and at the same time, a political form demonstrating the mobility and alliance based on the network of virtual connection. Until 27 October, this post has been reposted more than 154 thousands of times and there has been other circulation on platforms like Weixin. Like most people, I came across these images on the social media. Despite the fact that I was not in China, I was synchronised with the waves of information and mood on the Chinese Internet 简中互联网. When looking at the Weibo timeline filled with these images, I was speaking to myself, ‘this is the political moment in my generation.’

But I was also thinking, among all the mourning, why did this action and these images receive the most reverberation? Is this related to the fact that it was a physical action? Or because it has a slogan-like demonstration? When Butler discusses street politics, she emphasises the importance of embodiment. She asks, ‘could we still understand action, gesture, stillness, touch, and moving together if they were all reducible to the vocalization though speech?’ (Butler, 2015, 87) For me, this action Farewell to Li Wenliang reclaimed the right to physical spaces, to bodily actions as well as to silence. During the lockdown, the digital space was anxious, crowded and clamorous; if you don’t make a sound or type what your think, there would be no signal of your existence. When the man in black coat was lying down and gazing into the sky, there was the silence that could not be vocalised in another form. At the same time, this act was highly personal, as an individual’s creative response to the death of Dr. Li. It seems that he was not expecting a feedback, nor has he claimed authorship of the action. It is this personal and anonymous nature, combined with the penetrating and monumental form, paved the ground for the unpredictable publicness. It resembles to a grand political slogan in public spaces in China. But when realising that exclamation mark has been written by the man’s body, this slogan then is transformed into a resolute and decisive declaration. To some extent, it was an alarming reminder for people: right now, the most important thing is to say farewell to Dr. Li Wenliang, to pay your tribute, to say thanks for what he had done, to mourn for him.

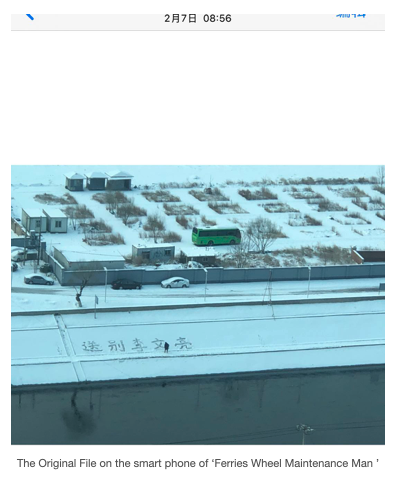

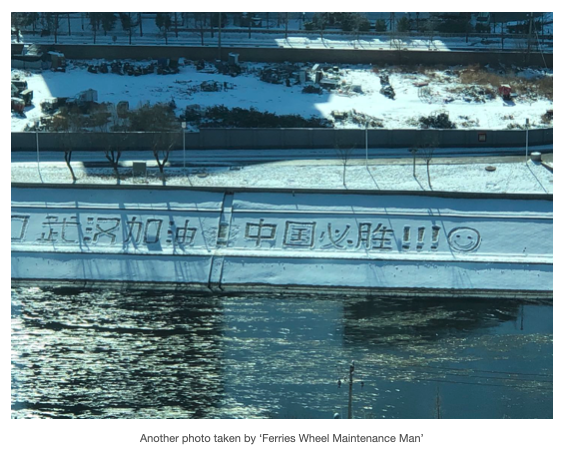

Despite this action has been widely circulated, the basic information about it has been unclear. People generally consider the account that posted the images is the author, but it was not confirmed. And we are not sure if there was any mediation between the action and the documentation. After some time of searching, I found the original author who took these photographs, a witness of this action, and I did an interview with her. She would love to be called as ‘Ferris Wheel Maintenance Man’ (修摩天轮的). She was a young photographer in Beijing and lived opposite to that riverbank on a high-rise. On the morning of 7 February, to be more accurate, 8:56 am, she spotted the action when it was ongoing, captured it with her smart phone and shared these photos with several friends. These images then spread through personal networks and when they were posted online nearly one hour later, this action became a national phenomenon. In this sense, the man who did this action, the photographer and people who shared it, are all contributors in transforming an anonymous and spontaneous action to an ‘event’ without any mediation. Later in that day, there were some bunches of fresh flowers left on that site. And in the afternoon, when the clouds in the sky dispersed, the photographer saw that man in black came back again. He stood by side of the characters, looking at it in the sunshine then and slowly walked away along the river. Later, more writings also came into existence on the riverbank, they were saying, ‘Go Wuhan’ (武汉加油) ‘China will succeed’ (中国必胜).

2

How this event has happened is not a mystery. But the action itself has a resolution and strength, which inspires me so much in thinking about art. This action itself did not take place in an art context; not all people consider it as art. For example, the photographer is against calling it art. In the following section, I want to first acknowledge this action does not claim to be an artwork, but I will then draw onto the strength of this work, to think about the suspicion and disbelief in art among Chinese artists and art-workers during the pandemic.

Among all the art genres that we could describe ’Farewell to Li Wenliang’, on-site performance and online art engagement might be the most obvious tags, but such clarification emphasises more on certain medium or about the platform like Weibo and Instagram. I would also call it as a performance, but I hope to position it into the history of Dada or the frenetic behaviours of ancient Chinese liberati like 阮籍, in the sense that it is expressing a political and social concern in a highly personal and creative approach. I hope to borrow scholar Jonah Westerman’s definition: performance is ‘a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world’ instead of a medium about body or acting. It is actually the undefined and nonconforming state of the work and its relation to the world, especially to me, it is my experience of being inspired and haunted by it, makes me claim this work is a brilliant artwork.

Back to February, China was the first country that fell into the state of national lockdown. For most residents in China, their lives were also suspended and I observed a widely spread suspicion towards art among Chinese artists and art workers when looking at Friend’s Circle on Wechat or Weibo. Some artists stopped their work because they could not access their studios; while some lost their faith in doing art. In late January, Art Newspaper Chinese sent out invitations to artists and asked if they could make a piece, do something or write something, many declined. A discussion was also heated, about Theodor W. Adorno’s famous sentence ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’. Many considered it as inappropriate to work on art and literature in a time of catastrophe. However, later when Europe and the US entered into the lockdown, I did not observe the same degree of suspicion or caution towards art. This led me to question, why did the Chinese artists feel awkward in the situation? How did the crisis of the society become an art crisis for these Chinese contemporary artists, according to my very biased observation?

What I am trying to make out of from the action ‘Farewell to Li Wenliang’, is not about whether this action is art or not, but rather, why artists should still trust in art. This action shows us that how much people are still in need of an imaginative, penetrating and healing expression especially in the time of difficulty; and how much hope and solidarity it could bring across isolation. It also reminds, great art, no matter it is made when facing the society or in solitude, all emerges from a profound and solid understanding to humanity and the world. If the photographer did not capture the action, if no one has seen it, if only the river and the sky have been the witness and the snow melted down and no trace of the words is left, will the power of this action be diminished? My answer is a clear No. It stands in its own history, responding directly to the death of Dr. Li Wenliang. The man in the black coat, no matter what happens, he is that bearer of his action. As for the audience, I think, we are just the lucky ones, sharing the power that he has inscribed into the snow.

Thank you.