As if the walls of

partition had become so thin…

On exhibition

Community of Feeling:

Emotional Patterns in Art in Post-1949 China

Curated by Su Wei

Assistant Curators: Huang Wenlong, Qian Mengni, Sun Gaorui

Inside-Out Museum in Beijing

Exhibition Dates: 2019.12.21 – 2020.5.24

Unpublished.

On exhibition

Community of Feeling:

Emotional Patterns in Art in Post-1949 China

Curated by Su Wei

Assistant Curators: Huang Wenlong, Qian Mengni, Sun Gaorui

Inside-Out Museum in Beijing

Exhibition Dates: 2019.12.21 – 2020.5.24

Unpublished.

At the end of 2020, looking back on the few exhibitions that I was lucky enough to visit, the one I have resonated most with during the isolated time in the lockdown amid the global turmoil, was ‘Community of Feeling: Emotional Patterns in Art in Post-1949 China’. It was curated by Su Wei at the Inside-Out Art Museum.[1]The museum’s name ‘Inside-Out’ reminded me that ‘Community of Feeling’ could also be read as an inward turning. While pushing the epochal propositions, such as revolution, into the background, it turns to the situations of individuals, focuses on the invisible and ephemeral emotions, and closely reads how art emerges from this messy ground.

It would take some time for an audience to dive into the large-quantity of materials: artworks from 48 artists and archival materials including photographs, films, handwritten letters and old journals, spreaded across the three-storey space. The space was like a reading room: visual objects evenly distributed, intersecting and echoing with each other, forming a modest polyphony. The bottom two floors presented works from the socialism period, and the top floor enlisted works which usually fall within the international phenomenon of ‘Chinese contemporary art’, positioned into a continuous narrative here with the former.

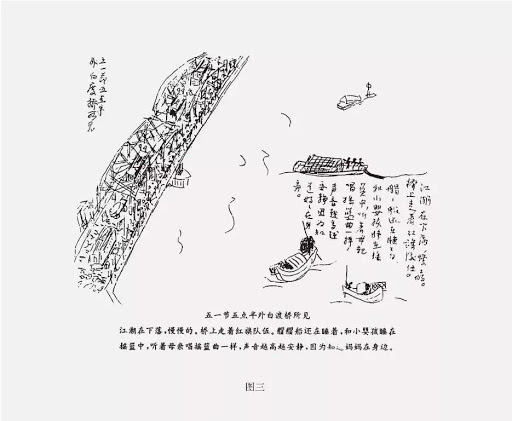

What is special about discussing emotion in the context of modern China is that it cannot shun away from its political and institutional re-appropriation. With Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art (1942), Mao Zedong set the new tone for socialist art: art that serves politics and is created for the proletariat — workers and farmers. ‘Emotion’ in art was then framed into themes such as revolution, anti-imperialism, and praise for industrial development. But the most obvious example of emotional mobilization — propaganda art — was not under review here. Instead, the exhibition took the situation of artists and intellectuals as its starting point. In the interaction between the artists and their environment, there were the artists’ genuine responses to the utopian calling and voluntary transformation, the negotiation with the mechanism such as the Artists’ Association, the debates on how to create art in the new social relations, as well as their spontaneous and unresolved feelings not yet identified. All these perspectives could be grasped by the rich meaning of the ‘Qing’ 情 in the Chinese title, which can be interpreted differently as ‘feeling’, ‘emotion’, ‘attachment’, ‘affection’, ‘sentiment’ or ‘self-consciousness’. Thus we could feel artists’ ecstasy in the success of the new China in 1949, manifested with a poem by Hu Feng 胡风 (1902-1985) about the inauguration of People’s Republic of China. Its lyrical title announces solemnly: ‘the time starts’. At the same time, there was also hesitation to embrace the collective passion. In a drawing completed in 1957 and shared through a private letter, the writer and researcher Shen Congwen 沈从文 (1902-1988) depicted a scene he saw through the window of his hotel room on a trip: a boat is drifting alone with a distance from the bridge packed with celebrating crowds and red flags on procession. Shen’s inscription reads wistfully that the boat is still floating ‘in dream’ and could not be awakened by the ‘sea of bustles’.[2]

Shen Congwen, 1957

The nuances and subtleties in emotion, which could not fit into the mainstream cultural framework, were given extra attention by the curators. In a section ‘Everyday Feeling’, there were the paintings by Zhao Wenliang 赵文量 (1937-2019) and Yang Yushu 杨雨澍 (1944-), two founding members of the loose underground group No-Name Art Group 无名画会 in Beijing during the 1960s and 1970s. In an art environment dominated by socialist realism, they cherished the beauties in nature and in their daily life, and empathised with the ordinary individuals who were not celebrated as heroes. In a still-life painting Green Pot drawn with thick strokes by Yang, we find a green pot sitting on a book, of which the cover is painted in bright orange. The high contrast in colour is by no means an accident. According to Yang, the pot is a symbol of a secure life which would allow him to paint without worry. And the unidentified book, in fact a catalogue of the prohibited Van Gogh, embodied his determination for art. Not far from this painting, a file cabinet exhibits a 1956 issue of the official journal Art. On the open page of the journal, an article asks in its title: ‘Can Everyday Trivial Things be Themes for Painting?’[3]The author considers such paintings about daily life to be incongruent with the demand for fine art — ‘highlighting the principle part with a systematic view’. For me, this is a fun part of the exhibition: all the abundant discursive and contextual materials are at your disposal to converse with the silent artworks.

Yang Yushu, Green Pot, 1973, 18.5×24cm, Oil Paintings on Wood Panel

Is there a ‘principle part’ in our life? What if ‘daily life’ and beautiful objects, for an artist, are the ‘principle part’? It is interesting to find that to emphasise the values of beauty and form, these concepts were given political agency through their relation with the need of the mass. For example, ‘Serving the Broadest Masses of the People’, an article in a relatively politically relaxed period of 1961-1962, signals the tolerance for art by using the terms like ‘mass’ and ‘people’ instead of ‘class’ and ‘farmers and workers’, which define the serving targets more strictly. Ironically, the artists’ pursuit of art, a natural trait of humans, could only obtain justification with this temporary extension.

As a Chinese researcher in contemporary art living overseas, I am unfamiliar with many artists and discourses in the socialist era. As it is said, ‘the past is a foreign country’. But different from some curatorial attempts that canonise figures and events as essential knowledge of art history, this exhibition paves the way to connect with the past through the lightweight ‘feeling’. This made me feel close to those historical moments by understanding why those artists, those ordinary individuals, were creating art. But going up to the top floor and looking at the contemporary artworks that I have been familiar with, the texture and contexts of the artworks were not presented as much as in the previous rooms. This is related to the change of framework, from solid interactions between the artists and the state, to a more abstract proposition of the relations between emotion and ‘conceptual art’. In the 1980s, the repressed emotion unleashed with the end of Cultural Revolution and the artists’ independence from the state’s sponsorship. We see harsh and intense expression in works like Ma Qiusha 马秋莎’s video From No.4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili (2007): as she talks directly to the camera about her suffering from the parents’ expectation, with her face sometimes twitched out of control. At the end of the film, she pulls out a razor blade, already bloodied, as if it is a revenge or a liberation. There are also detachment, observation and sarcasm for new social progresses like globalisation, urbanisation and marketisation. For example, Hong Hao ’s Selected Scriptures (1995) satirises his peer Chinese artists’ desire of going to the Documenta. These works are presented in juxtaposition with the conceptual practices outside China, such as Andy Warhol’s sensual and touching video Kiss,and echo with theoretical propositions exemplified by Ellen Seifermann’s ‘Romantic Conceptualism’. Although such connection broadens the geographical scale, it still lacks a connection between the contexts of the artworks and the curator’s question. Whereas in the socialism period, the first-hand materials and the detailed contexts allow me to encounter the artists directly, and the framework emerged naturally in this engagement. It was as the name of the space, ‘inside out’, suggests: the vein embedded in the art reveals itself and embodies a clear form in the audience’s understanding.

Screen short of Ma Qiushsa, From No.4 Pingyuanli to No.4 Tianqiaobeili,

Single channel video. Color, sound, 7'54''. 2007.

During the first lockdown, I followed the ‘close-reading’ series of the exhibition published on the museum’s digital platforms. In those artists’ circumstances, I see my contemporaries and myself. I see the intensified fear, anger, suspicion, bravery, and resolution amid the turmoil across time and locality. There is also the unresolved feeling: despite that I joined the ‘Black Lives Matter’ protest, a part of me as a Chinese was still not sure how I should relate to this movement with my reservation about collectivism. As I was marching on the street, the Chinese title of the exhibition, a lyrical verb I would just translate as ‘Start to Feel’, came to my mind — yes, at least I am awake and I am feeling what it means to be one of the plurals. As Woolf whispers, ‘as if the walls of partition had become so thin that […] it was all one stream...’

[1] The Chinese title for the exhibition is ’动情:1949 后变局中的情感与艺术观念‘. It was curated by Su Wei 苏伟 with curatorial assistance from Huang Wenlong 黄文珑, Qian Mengni 钱梦妮 and Sun Gaorui 孙杲睿.

[2] The original inscription is ‘艒艒船還在作夢,在大海中飄動。原來是紅旗的海,歌聲的海,鑼鼓的海。(總而言之不醒。)’. This has been further discussed in David Der-wei Wang, ‘The Three Epiphanies of Shen Congwen’, in The Lyrical in Epic Time: Modern Chinese Intellectuals and Artists Through the 1949 Crisis(Columbia University Press, 2015), pp. 79–112.

[3] Ren Zhiming 任志明, ‘Richang Suoshi Keyi Zuowei Huihua de Zhuti Ma [日常琐事可以作为绘画的主题吗 Can Everyday Trivial Things Be Themes for Painting?]’, Meishu [Art 美术], 5, 1956, 12–13.